Feathers on the Flyway: Unraveling Avian Mysteries at Bear Divide with the Moore Lab

Visiting Bear Divide between mid-April and mid-May, when thousands of migrating birds funnel through the pass at dawn, is an ideal experience for any birder.

Editor’s note: The peak migration period at Bear Divide in the San Gabriel Mountains typically occurs between April 10 and May 20, making this the optimal time to visit. During these weeks, species such as Western Tanagers, Lazuli Buntings, and various warblers can be observed in impressive numbers. Early morning visits are particularly rewarding, as the majority of migratory activity happens shortly after sunrise.

“Personally, I really think it’s one of the best birding spots in the world,” Ryan Terrill, science director at the Klamath Bird Observatory.

Within a 45 minute drive from the urban chaos of downtown Los Angeles, lies a natural, ornithological marvel: Bear Divide, a vital corridor for the annual migration of numerous bird species. Every year — roughly between March 15 and June 15, with peak migration between April 10 and May 20 — thousands of birds funnel through the narrow pass. The divide is a small dip in the otherwise impregnable San Gabriel mountains, allowing birds in the midst of their migration to pass through safely at relatively low altitudes. This area is not just a haven for bird enthusiasts but also a critical research site, especially for the team from the Moore Lab of Zoology at Occidental College, who have been delving into the intricacies of these migratory patterns.

The Moore Lab of Zoology is renowned for its extensive bird specimen collection, one of the largest of its kind in the world for Mexican birds.

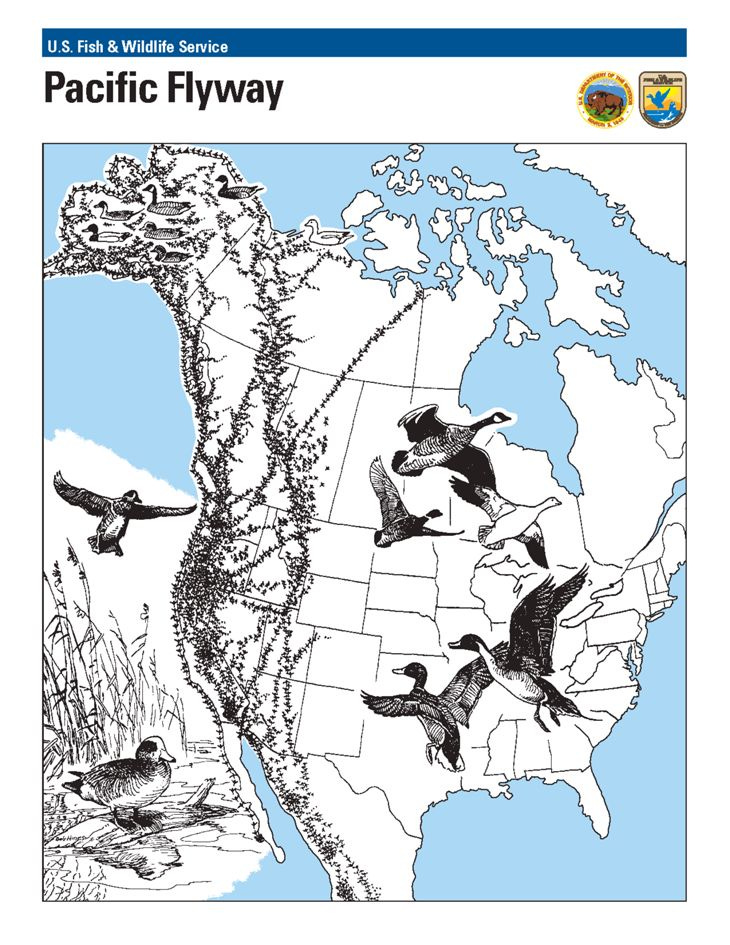

Bear Divide is strategically positioned along the Pacific Flyway, a significant north-south migratory route used by birds traveling between Alaska and Patagonia. The geographical features of the San Gabriels provide an ideal resting and feeding ground for these birds, making Bear Divide a crucial stopover during their long journeys. It's this unique combination of location and topography that makes Bear Divide an essential component of avian migration.

The discovery of Bear Divide was a lucky happenstance. A bird researcher was conducting overnight monitoring in the spring of 2016, and when morning came, he noticed legions of small songbirds whizzing past his monitoring spot. His report caught the attention of postdoc bird scientist Ryan Terrill at Moore Lab at the time, and he began an effort to monitor the birds. Terrill and his team would ultimately record as many as 20,000 birds in a single morning.

“It really is overwhelming to stand on the road and have 5,000 birds of 80 species fly by your knees in a morning,” Terrill said. The effort has continued to this day with startling results. Terrill has since left and is now the science director at the Klamath Bird Observatory.

"In 2023 we counted 53,511 birds of 140 species from February to May," said John McCormack, a professor of biology and the Director and Curator of the Moore Laboratory of Zoology. "And of course, we missed many thousands more because most travel at night. It's easy to say that there are hundreds of thousands of birds passing through Bear Divide."

As many as 13,000 western tanagers, lazuli buntings, chipping sparrows, hermit warblers, orioles, grosbeaks and warblers pass through Bear Divide on a single day. Why they do so, is not entirely understood. The unusual topography of Bear Divide essentially serves as a funnel for the migrating birds, with many of them shooting through the gap just a meter or two above ground.

“Personally, I really think it’s one of the best birding spots in the world,” Terrill told the LA Times.

McCormack says that the "ultimate goal is to better understand the Pacific Flyway and how it's used, especially by small terrestrial birds. Little is known about their movements because they are hard to see and usually travel at night."

Because many of the species sighted at Bear Divide are in steep decline. The lab says that year-to-year counts will help set a baseline for future trends that can be associated with weather, climate, and urbanization. "Tracking individual birds will give granular knowledge on how migratory birds use the landscape, which helps individuals and homeowners create corridors for them to travel," says McCormack.

The best time to catch the show at Bear Divide is late winter early Spring. McCormack says Cliff Swallows and Lawrence's Goldfinch are some of the early movers in March, and that by May, streaking by are Yellow Warblers, sunset-faced Western Tanagers, and bright blue Lazuli Buntings.

“There is so much we still don’t know about these birds and their world,” Lauren Hill, the site’s lead bird bander, told the Los Angeles Times. “For example, no one knows where they were before showing up here after sunrise.”

The team is counting birds in order to establish a baseline of the populations coming through Bear Divide so they can understand how much we are changing the environment and what effect that may have on bird populations, many of which are in severe decline.

Their research spans a variety of topics, including how climate change is impacting migration routes and the effects of urbanization on bird populations. The lab has recently begun a program to put satellite trackers on birds at Bear Divide to follow individual birds, providing deep insight into their migration and resting patterns.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Bear Divide is the sheer variety of bird species it attracts. From the diminutive hummingbirds to the impressive birds of prey, each species adds a unique dimension to the study of migration. The Moore lab's findings have shed light on the varied responses of different species to environmental changes, offering a glimpse into the broader ecological shifts occurring across the globe.

One compelling result of the Moore Lab's study at Bear Divide suggests that the peak of a particular species’ migration is correlated with the latitude of its breeding site. Species that breed at higher latitudes migrated through Bear Divide at later dates. It's also unusual in the West for species to migrate during the day. Most species of birds using the Pacific Flyway are known to migrate at night.

In addition to its scientific contributions, the Moore lab is also known for its involvement in citizen science. Collaborating with local birdwatchers and volunteers, the lab extends its research capabilities and cultivates a community actively engaged in bird conservation. This collaborative approach not only enhances the breadth of their research but also underscores the importance of community involvement in conservation efforts.

Bear Divide is on public land, so anyone with a legitimate research project can get permission to work there. UCLA graduate student Kelsey Reckling, who has worked as a counter at Bear Divide since the beginning, is leading the counting efforts this Spring to understand changes in numbers of birds and species across years. Cal State L.A. graduate student Lauren Hill lea ds the group of bird banders, who catch some of the birds and record data, attaching a lightweight metal band around one leg and releasing them. Her lab mate Tania Romero is putting small, lightweight tracking devices on Yellow Warblers, which send signals to a network of tracking (MOTUS) towers across the continent.

According to a 2019 study, nearly 3 billion breeding birds have been lost in North America and the European Union since 1970. That's about 30% of the bird population in North America. The 2022 State of the Birds Report for the United States found that bird declines are continuing in almost every habitat, except wetlands. Protecting birds' habitats, and migration routes and reducing mortality through conservation efforts are crucial to ensuring the survival of these magnificent creatures.

"What's magical about Bear Divide is that it's the first real place to see small, migrating birds at eye level in daylight hours," says McCormack. "I don't want to oversell it: it's still a lot of small birds zinging by in a wide open place and it takes a while to get good at identifying them. But by seeing them out there, struggling against the wind and the cold, but still making progress, it gives you a real sense of how amazing their journeys are--and how we shouldn't make them harder if there's anything we can do about it."

great story!

I like how so many birds go through this specific area. It's a way station on their bird road trip.